Jaime Garzon's Colombia: a nation through

the work of a prophetic humourist.

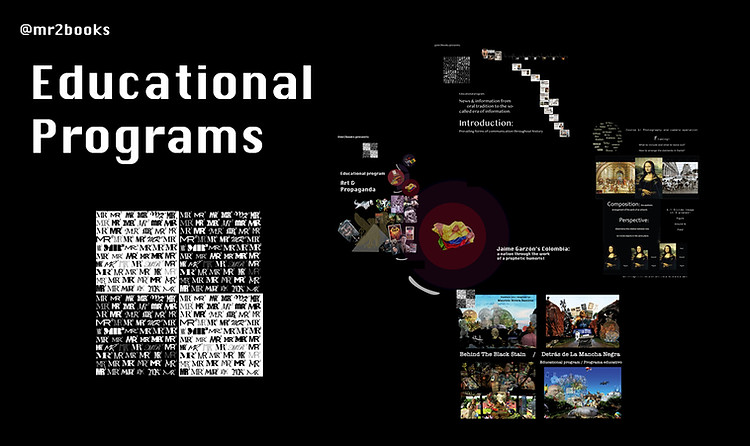

@mr2Books - Educational Programs

This short program is an extension of: the program Art & Propaganda

Introductory note

Jaime Garzón was shot dead in Bogotá on August 13, 1999. This short educational program was originally conceived as a case study, of how art can be preserved in the collective memory through different technological eras, as Garzon worked in television, but his legacy continues to influence new generations through digital media. It is based on some of his comedic sketches available in Youtube and also on extracts from a conference at the Corporación Universitaria Autónoma de Occidente (Cali, COL) in 1997.

Godofredo Cínico Caspa and the Colombian traditional parties

One of Garzón’s most popular characters was Godofredo Cínico Caspa: an old-fashioned, hard-lined, conservative lawyer. In the sketch presented below, he speaks about the right to vote in Colombia.

"You are being addressed by Godofredo Cínico Caspa: last bastion of our national dignity and decorum. In these days our honourable republican congress has been debating about the so-called ‘obligatory vote.’ Since when do our rulers want to popularize a right, a right and a privilege of the righteous people?[1]

"I do not understand why they fail to refer to the fountains of democracy and the rivers of tradition and consult the constitutions of the nineteenth century: which stated that those with the right to vote were only men, over 35 years old, married, with an income greater than 1,500 pesos and who could demonstrate acts of intelligence. Since when are women allowed to vote? May they leave the polls and return to the kitchen. It’s not O.K. for communists and opposites to have the right to vote. When did we allow this to happen? The righteous people should be electing the righteous people. We might be few, that’s evident, but with dignity and discretion we shall elect our rulers. What the hell, Álvaro and I will end up electing the president of 1998. Good Night![2]

[1] translated from 'gente de bien'.

[2] sketches translated by Mauricio Rivera R.

Symbolism

Godofredo addressed the nation from his office, which was full of books and folios. This is a reference to the abundance of laws and a criticism of the bureaucratic nature of the Colombian legal system. The lighting in Godofredo’s office fades from the red to the blue. This is an allusion to the Colombian traditional parties: the Liberal Party (historically represented by the colour red) and the Conservative Party (historically represented by the colour blue).

When Godofredo talks about the constitutions of the nineteenth century, he is referring to a period in Colombia’s history that was marked by a succession of constitutional changes, followed by a succession of civil wars (see the table below).

Civil Wars & Constitutional Changes

Colombia: 19th century

Civil war

-

War of 1831 between centralists and federalists.

-

1840 War of the Supremes a.k.a. War of the Convents (Guerra de los Supremos o de los Conventos).

-

War of 1854: between the “Golgotas” (traders and defendants of free-trade) and the Draconianos (artisans defendants of protectionism).

-

War of 1860-1862: Conservative / Centralist government vs. Liberal / Federalist opposition.

-

War of 1876-1877: division in the Liberal party between the radical Aquileo Parra and the moderate Rafael Nuñez.

-

War of 1895: Against the presidency of Rafael Nuñez who on this occasion was president from the Conservative Party.

-

1.000 Days War: 1899 -- 1902

Constitutional change

-

Constitution of 1832: constitution of the Republic of Nueva Granada and installation of a presidential & Centralist regime; Santander elected as president.

-

Constitution of 1843: radicalisation of Centralist politics.

-

Constitution of 1853: first Federalist constitution.

-

Constitution of 1858: Centralist by nature, “Confederación Granadina” is the new name of the county.

-

Constitution of 1863: federalist by nature, “Estados Unidos de Colombia” is the new name of the county.

-

Constitution of 1886: which lasted until 1991 and was conservative by nature (i.e., acknowledged the relationship between the state and the Catholic church, was centralist and was economically protectionist.

During the 19th and most of the 20th centuries, Colombia was rigidly bipartisan (until the creation of socialist and/or Marxist guerrillas in the 1960s and later with the proliferation of drug-dealing mafias in the 1970s and 1980s). Hence, political sectarianism was the main cause of violence.

The wars between Liberals and Conservatives have been a constant reference in many artworks from Colombia’s republican history: including One Hundred Years of Solitude. In one passage, Colonel Aureliano Buendia (before becoming a leader of the Liberals) is talking with his Conservative father-in-law: Don Apolinar Moscote, who latter describes the main ideological differences between the two parties in the following terms:

"The Liberals (sic) were Freemasons, bad people, wanting to hang priests, to institute civil marriage and divorce, to recognise the rights of illegitimate children as equal to those of legitimate ones, and to cut the country up into a federal system that would take power away from the supreme authority. The Conservatives, on the other hand, who had received their power directly from God, proposed the establishment of the faith of Christ, of the principle of authority, and were not prepared to permit the country to be broken down into autonomous entities." (p. 98)[3]

Nonetheless, as García Márquez also pointed out (right after the previous description), beyond the ideological differences Colombia has been ruled by a small elite. This dynastic political order is evident in the lineage of numerous presidents, such as: Juan Manuel Santos (elected in 2010) who is the grand-nephew of former president Eduardo Santos (president from 1938 to 1942); or Andrés Pastrana (president from 1998 to 2002) who is the son of former president Misael Pastrana (president from 1970 to 1974).

[3] from 1970 translation by Gregory Rabassa

John Lenin and the orthodox left

The opposite character to Godofredo Cínico Caspa is the left-wing, militant, public-university student John Lenin. In the sketch presented below, he speaks about the relation between the US and Colombia, particularly in regard to the traffic of narcotics.

"The gringos’ tails are made of straw and their noses full of powder compañeros! Besides, from snorting it all, they also want to get into our huts[4]; which might be also made of straw, but are as honourable as the sweat of the oppressed peoples compañeros! Because the enemy sees the straw in our wagon[5], but fails to see the cosa nostra sticking out of his imperial eagle-eye compañeros! Behind every ‘traco-democracy’[6] there is a ‘narco-imperialism’ compañeros. Look at the case of Dukakis and Gore compañeros, who have the snow of corruption upon their shoulders, in the sense that they get closer to power with the ‘narco-dollares’ given to them by our ‘narco-paisanos.’ Against the drugs, may the gringos snort them all! Thank you compañeros."

[4] translation of 'metersenos al rancho,' meaning something like: to step into our business.

[5] wagon is the translation of 'carreta', which in Colombian slang means small talk or gibberish.

[6] traco=traqueto, term used in reference to a small-time drug dealer.

Context

This sketch follows on the idea of Yankee Imperialism exposed in Garcia Marquez’ account of The Massacre of the Banana Fields, and presents the traffic of narcotics and the so-called War on Drugs, as the latest episode of what may be interpreted as a neo-colonialist relation between the USA and Colombia (and by extension other drug-producing and/or exporting countries like México, Perú, Bolivia and Venezuela).

As shown in the sketch, behind John Lenin, there is a graffiti that reads “Extra Adicción para los Gringos” [Extra-Addiction for the Gringos]. Here, Garzón is playing around with words in order to make reference to the extradition treaty that marked the relations between Colombia and the US in the late 1980s and early 1990s (which led drug lord Pablo Escobar to declare war on the Colombian State).

Dioselina and Nestor Elí: servants of power in Colombia

Garzón created Godofredo and John Lenin while working in the TV show Quac!, which was a parody of a newscast from the mid-1990s called QAP. During this time, he also portrayed Dioselina Tibana and Nestor Elí. Dioselina was the maid at the residence of the Colombian president. Nestor Elí was the doorman of the fictional Colombia Building.

Context

Quac! aired during the presidency of Ernesto Samper (1994-1998). This government was marked by a scandal known as the 8,000th process: where it was proved that Samper’s presidential campaign had been financed by members of the Cali Cartel.

At the end of Samper’s government, the guerrilla groups in Colombia, particularly the FARC, grew in number and strength, shifting their strategy from guerrilla warfare to holding a positional army. During this period, the FARC managed to seize power in many peripheral regions. This rise of the guerrillas can be explained by the fact that, unlike most Latin American guerrillas from the 1960s and 70s that vanished with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Colombian guerrillas found in the traffic of narcotics a source of income that has proved to be more reliable than aid from the former Soviet Union.

Between 1996 and 1998, the FARC reached its maximum military and political power since its creation in 1964. During this period, they struck the heaviest blows on the Colombian armed forces, and also began a practice of indiscriminate kidnapping of civilians that ended up turning the population against them (and, as exposed in more detail a few paragraphs below, also led to a general support of right-wing policies and ideologies that matched the rise of Alvaro Uribe’s popularity).

Samper was followed in the presidency by Andrés Pastrana. After losing the 1994 election, Pastrana was the person who revealed the audiocassettes that were the original evidence of the infiltration of drug-related money into Samper’s presidential campaign. In 1998, Pastrana came to power with the promise of organising a peace process with the FARC. This process began on January 7, 1999, and was ended by the government three years later, after the FARC seized an airplane that had departed from the city of Neiva and kidnapped the senator Jorge Eduardo Géchem, on 20 February 2002.

Jaime Garzón had a personal relationship with Pastrana, as he had worked as chief of tours when Pastrana was campaigning for Mayor of Bogotá in the late 1980s. During this time, Pastrana was kidnapped by Pablo Escobar’s Cartel of Medellin. Garzón was there at the time Pastrana was seized.

Heriberto de la Calle

During the first years of Pastrana’s presidency, Garzón created one of his most popular characters, the shoe polisher Heriberto de la Calle. Dressed as Heriberto, Garzón interviewed different personalities from Colombian public life while polishing their shoes: from politicians to celebrities and sports figures. In one of them, Garzón interviews Fabio Valencia Cossio: a political leader from the Conservative Party, who at the time was a congressman and would later become Minister of Interior and Justice during Álvaro Uribe’s government. The following is an extract from this interview:

Heriberto de la Calle (HdC): “Look Dr. Valencia I had to tie up my shoe polish (…) because there’s a lot of politicians coming here.”

Valencia Cossio (VC): “That’s why I wear sneakers… (laughter)… I heard rumours they are kicking you out.”

HdC: “Kicking me out of the newscast?”

VC: “Yes, because you are too much of a hassle, and people don’t like it.”

HdC: “But who am I hassling Dr Valencia? Nobody. I’m just repeating what I hear in the neighbourhood; for instance about the AUC: they say the biggest electors in the country are ‘el Mono Jojoy’ and Fabio Valencia Cossio.” [7]

In another interview, Heriberto is polishing the shoes of his former boss, the then presidential candidate, Andrés Pastrana. The following is an extract from this interview:

HdC: ”You know something else Dr. Pastrana, when you’re sitting over there (meaning in the presidential seat), you have to be aware of the paramilitary. How come the army passes by, then the police passes by and a few moments later: Boom! Someone wipes out 14. How’s that possible?”

Pastrana: “Strange isn’t it?”

HdC: “I’m just trying to help. So don’t say I didn’t tell you so; you know, when they are kicking your ass.”

[7] AUC = Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia: name of the largest paramilitary group formed in Colombia in the late 20th century. Victor Julio Suárez a.k.a. El Mono Jojoy was a former FARC commander, killed on 22 / 09 / 2010.

Garzon's prophecies

As mentioned before, the failure of the peace process with the FARC led the majorities in Colombia to shift towards the right and ultimately elect the candidate that personified the thirst for retaliation against this guerrilla: the former governor of Antioquia Álvaro Uribe Vélez.

On February 11, 1994 (during the last year of César Gaviria’s presidency), Congress passed a law that authorised the formation of neighbourhood watch groups named Convivir. Between 1995 and 1997, when Uribe was governor of Antioquia, he became the main promoter of these organisations. Since that moment, Jaime Garzón was critical of these groups, which were often related to the paramilitary that had been forming all over the country since the 1980s.

In the sketch studied above – where Godofredo speaks about the right to vote in Colombia – Garzón refers to Álvaro Uribe as a member of what he called the righteous people. Below, in another of Godofredo’s sketches, he focuses on Uribe.

"What national pride did I feel when I saw the cover of Semana Magazine showing the image of the pacifist, cooperativist and most dignified governor of Antioquia: Dr. Álvaro Uribe Velez. A man with a strong-hand and an armed fist; a leader who, with his mighty cooperativism, impulses peaceful ‘self-defence-groups’; which he, enlightened by the sons of Faruk, has decided to name Convivir. The magazine is right in projecting over the national arena the light of this neo-liberal genius. Álvaro can fit the country inside his head; he foresees this great nation as one big zone of total public order: in other words, as one big Convivir. Where the righteous people may finally enjoy our rents in peace, the way it should be. And it shall be him who will finally bring the redeeming North American soldiers, who will humanise the conflict and make of Uribe Velez the dictator that this country needs! Good night."

Garzón also satirised the Colombian armed forces. This can be seen in the video embedded below, which includes two sketches from Quac!, and a short extract from the conference in Cali. Throughout this video, in-between the selected footage – there are titles where, whomever edited it, accuses Uribe of promoting paramilitarism in Colombia and refers to the armed forces as “pawns in Uribe’s political chessboard” (the clip was uploaded to YouTube on April 5, 2007, by the user reyes300; the video has no credits).

In the aforementioned conference in Cali (which took place in 1997), Garzón acknowledged what at the time was a slight rise in Uribe’s popularity, which he believed to be “very dangerous”. There is also a moment, when someone asks him about the role of NGOs and, while stating the risks of being independent, he ends up talking about the threats that he was receiving (two years before of his assassination).

"Independence has a price, and that price is to subject oneself to something … take me for example, I’m not truly independent, I’m just making jokes, and yet they keep calling my house and leaving messages saying, ‘we know where you live, we are going to cut your tongue’ and so forth. Everyday. That’s my daily bread. That changes one’s life. For instance, I now change my underwear everyday. Of course, imagine the corpse all shat down. I’m not afraid they won’t recognise me, because who else has teeth like these… But life’s changes and every morning you end up grooming yourself for death."